Creative Writing Program Reading Series. October 5th, 2017. University of Tulsa, Tulsa, OK.

Notations Series Visiting Writer. April 28th, 2017. Zoellner Center for the Arts, Lehigh University, Bethlehem, PA.

Faculty reading and book signing. July 3rd, 2017. La Ateneu Barcelonès, Barcelona, Spain.

Author Spotlight. March 7th, 2016, 7:00pm. Jean Cocteau Cinema. 418 Montezuma Ave, Santa Fe, NM.

Reading and book signing. June 29th, 2015, 7:00pm. Favoritenstrasse 4-6/1, Vienna, Austria.

Reading and book signing. November 18th, 2014, 8:00pm at Andú, Carrer del Correu Vell, 3, 08002 Barcelona, Spain.

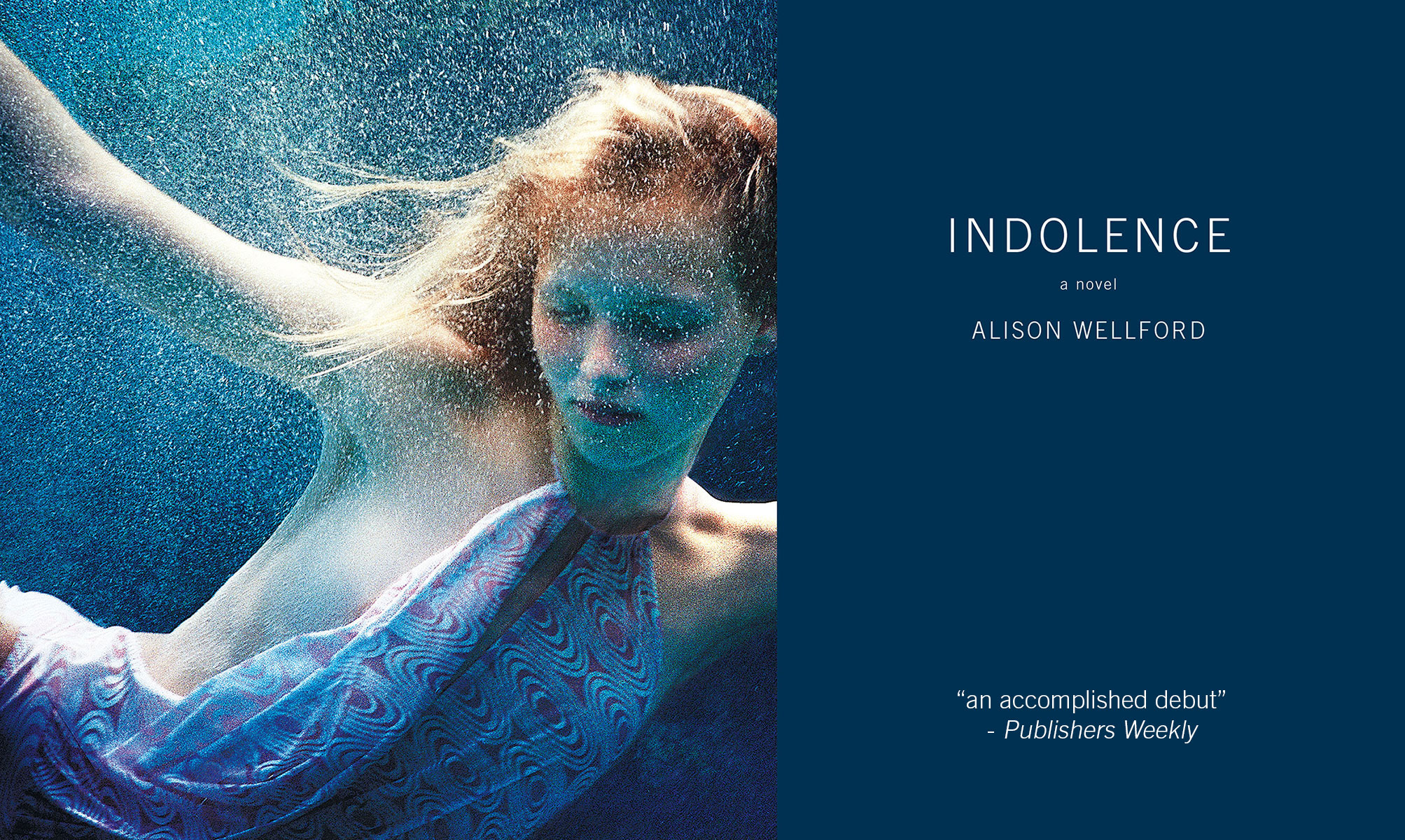

Outpost 19 announces early-bird paperback orders of INDOLENCE. Available now. Purchase by August 27th and receive delivery by September 15. Click here to order!

INDOLENCE by Alison Wellford. Sixteen-year-old Maria returns to her parents' home in the French countryside. Her ill mother faces her last days and her preoccupied father has grown even more distant. In the shadow of her parents' sorrow, Maria pursues a much older man, a disreputable art collector. She is infatuated with him, as with the French paintings she has come to love. Maria enters a world of tenderness and captivity, of transgression and awakening, and of art and sensuality. Lyrical, painterly and erotic, Indolence is a portrait of a young girl's haunting passage into womanhood.

"It's rare to read a debut as extraordinary as Indolence by Alison Wellford; it's one of the sleekest, bravest, and most explosive first novels I've read in years. Indolence's tremendous achievements lie in the gorgeously wrought prose and a moral ambiguity so perfectly deployed that, even months after having read the book, I feel haunted by Wellford's strange and lovely work."

—Lauren Groff, author of Arcadia; The Monsters of Templeton; Delicate Edible Birds

"In this debut novel, gorgeously set in the south of France, Alison Wellford captures a story as passionate and elemental as a Greek myth in breathless, painterly prose. Maria's voice becomes that of all those nudes in countless paintings by men, the voice of prostitutes and child-lovers, of women giving their bodies in the streets and dying of tuberculosis as they are rendered radiantly immortal. Indolence, the story of a young woman’s sensual and sentimental education, is a profound and beautifully written novel."

—Naeem Murr, author of A Perfect Man; The Genius of the Sea; The Boy

"A sensual, complexly intelligent tale about the daughter of ex-pats in France who loses her mother and enters an underworld of sex, transgression, and fantasy. Erotic and aesthetically rich, every page of Indolence is charged with icy passion and beauty."

—Jane Alison, author of Change Me: Stories of Sexual Transformation from Ovid; The Sisters Antipodes; Natives and Exotics; The Marriage of the Sea; The Love-Artist

Alison Wellford published the novel Indolence and wrote the screeplay adaptation, which was optioned for film. Her short fiction has appeared in The Gettysburg Review, The Barcelona Review, and Fence, among other journals, and was nominated for a Pushcart Prize. She has received fellowships from The Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, The MacDowell Colony, and the Barbara Deming Memorial Fund. She is assistant professor of writing and Pan-European MFA program director in creative writing at Cedar Crest College.

Wellford's accomplished debut offers a portrait of a May-December romance, which comforts a vulnerable young woman—until it doesn't. Sixteen-year-old Maria, resentful after being enrolled in an American boarding school while her mother convalesces in the French countryside, returns home for summer vacation. Her mother's cancer, however, is more advanced than Maria knew, and her father's anxiety manifests itself as deliberately distant, "noxiously quiet." Feeling adrift and underfoot, Maria fixates on Omar, a much older man who has expressed interest in her. Her advances are soon returned, and the two embark on a love affair that eventually cuts Maria off even further from her family. Omar, an art collector living in a ramshackle house, offers more than an erotic education for Maria—but at the novel's end, it's unclear, even years after the affair has ended, whether or how Maria's growing interest in art and artists will shape her adult life. The novel's appropriately languid tone and expressive descriptions, particularly of the natural world, offers an impressionistic portrait not only of Maria's surroundings but also of her state of mind. Maria's voice not only carries readers through these pages, but will stick with them afterward. —Publisher's Weekly

![]()

If you loved Lolita, you will love Indolence, the debut novel from Alison Wellford. Unlike Nabokov's gem, however, Indolence isn't hilarious, but it is taut, fresh, lyrical, and constantly engaging.

Set mostly in the south of France, Indolence delivers the voice of Maria, a highly intelligent late teenager struggling with the woes that all late teenagers face—boredom, ennui, alienation. It's a long solitary summer, filled with her parents' drunken parties and her mother's brutal terminal illness, which will take her life near the end of the season leaving Maria with both her own grief and the grief of her father. For such reasons she finds herself wishing for some other kind of life, and she finds it in Omar, a family friend and neighbor, a much older man who is an art thief. At least forty years her senior, he attracts her with his sophistication but also with the sense of transgression that attachment with him seems to offer. She "disappears" and runs away with him.

Together they embark on a journey of stasis, of constant sex, of hiding themselves in his house, ironically so nearby her family home.

"More than the sex there was the sun coming through the window onto our faces, the sun that sunk each day in an entirely different way, the candles he lit for me and their flames tossing ruby prisms through glasses of red wine on the wooden table onto the dinner he prepared for me from the vegetables we had grown in the garden, the red bell peppers that had small green infants inside—the simple, domestic acts of being together."

In this way Indolence transforms from a Lolita updated to the Lolita's perspective into a book of considerable poetry, sensuality, and wonder. "Love meant being together," Maria says, in the thick of her time with Omar. "My parents had not understood that?"

However, like all things teenager, this affair runs its course, broken off though not by Maria herself, but by the ever callous and manipulative Omar. When she learns he has locked her in only to abandon her, she escapes to Spain, and years pass in which almost nothing happens to her. From time to time she gets wind of her father's despair in the face of her disappearance, but she has been desensitized to suffering. Only at the end, when her perfunctory job vanishes much like she did, does she begin to make her way back toward him.

It's a raw, powerful, disturbing and deeply resonant book, beautifully structured in an inverse countdown of chapter numbers that summons the memory of her mother putting her to bed as a child. And at the end of this countdown, when Maria finally returns to her father, she notices that "His face is full of love. I can barely look." Yet all along she has allowed us to look at her so closely, to judge her and to empathize with her, that we understand her so well that we just want to keep looking as she completes her remarkable journey. Indolence, simply put, is a dazzling novel. —The Barcelona Review

![]()

Alison Wellford’s first novel, Indolence, is told in the first person by Maria, a sixteen-year-old American girl whose parents live in the South of France. She tells of her sexual awakening, passion, domination and attachment to an older man, Omar, at a time of intense emotional upheaval over the summer and autumn when her mother dies. The writing is at times painful – it is raw, yet innocent and totally credible. One may not like Omar but the narrator certainly does. She does not hide his faults but ascribes these generally to traits of character – how he is.

Omar himself could be a stumbling block to enjoyment of the novel but the treatment of his character is largely sympathetic, seen through Maria’s eyes. She is attracted to this elegant older man who wears beautiful clothes and knows so much about art, especially Impressionism (with its links to the area of France where they live). That he is half-Moroccan, has been an art dealer and mixes in the shady world of art theft makes him even more attractive. He decently refuses her first (perhaps semi-innocent) approaches but not her direct ‘assault’ in his own home:

I marched to his door. He was hiding inside. I knocked. No answer. I kicked the door but then stopped. I was afraid. Answer the door. Don’t answer the door.

When I looked up, his arms were crossed, his hips jutting out. He could not have known [that her mother had just died] but he reached out and held me as if he did. We kissed, a too wet, a too thick kiss.

Maria’s first sexual experience is recounted minutely, matter of fact: “I wasn’t sure how long we’d kiss or what to do next.” She watched a spider’s web, wafted by the ceiling fan: “Sex should’ve changed everything.” (But she doesn’t say if it did.) “He fell directly asleep for a time and I waited.” Not romanticized:

There was a stain on the bath where I had been sitting, like the stain on the bed, and I turned away in embarrassment.

"You’ve never been with a man," he said.

He was gentle with me in the bath, not like he was in the bed, almost apologetic, and I wondered if that’s how all men loved their women, and if it would change next time, if I would ever be the one to lick the wounds I had inflicted upon him. Of course I hadn’t been with a man.

Erotic images drawn in words by Maria accompany reproductions of erotic images from Omar’s extensive collection of art books: first Klimt, then Bonnard:

It was a painting of a naked girl on the bed, her legs open, just a floss of hair there and some strange diaphanous smoke, or a scarf, floating above her thigh. Her arm was draped over her breasts, her hair flowing behind her, the bed tilted as if you could enter the painting – an invitation … the girl revealing nothing about herself but her sex, locked up in some great interior mystery, but maybe that was the mystery of youth, of her being just a bud of a girl, that her life had yet to take hold of her, and in fact, was about to happen.

The painting was of Bonnard’s wife, Maria, entitled Femme assoupie sur un lit (woman asleep on a bed) or, particularly relevant here, L’Indolente (the idle girl). Later, we see works by Chagall and Balthus, Cézanne, Manet.

As we follow Maria’s account of her summer, we learn about her father and mother, of their shared love and protective environment, her frustration and sorrow at being kept at boarding school in the States, of her poor school results, lack of friends, awkwardness when offered friendship by Annie (to whom she writes unposted letters later – an almost friend). She is a sensitive yet tough young woman who survives.

At the funeral of her mother, Caroline MacVeigh, the priest emphasizes that she was a wife and mother, the greatest gift to the world. “There was a burning in my chest and the shadows behind us felt heavy and the light was thick, and I knew it was a moment in which something was happening, my mother was dead, but this realization didn’t make it any more real to me.” At the funeral and at several other points in the novel, we are told how much Maria resembles her mother physically and we see in her writings, imagination and love for Omar that this is truly so.

Maria feels guilt at her behavior towards her parents: the shocking last conversation with her mother, her disappearance from her father. She matures throughout the telling of her story. She does not feel guilt for her behavior with Omar because, she says, this is something of her very own. She does need to feel in control of the relationship, however, and when this is no longer possible, she acts: “Each painting was a window to somewhere else, but now I was inside. I had to think about an exit and I worried that once I left, I would forever mourn this place …”

Indolence has connotations of wishing to avoid trouble, love of ease, laziness, avoidance of responsibility, disinclination to exertion – all of which we find in the novel. At the party at the beginning of the summer, Maria’s mother calls Omar “the do-nothing king” and Maria picks this up, in her autumn hiding, calling their couple: “le roi et la reine-fainéante.” A secondary, medical, meaning for indolence is that of freedom from pain or suffering – which is I think the narrator’s goal: deliverance from suffering caused and experienced. —reviewed by Susan Jupp, Necessary Fiction

Or please direct questions to Outpost 19.